Languaging Trails of Sound and Light

JOHN ROBERT CORNELL

Language is breath—specially formed bursts of air from the lungs. Like breathing, language is mostly automatic. Word sounds come sliding and tripping out, bypassing reflection about grammar or pronunciation. Writing cascades down the arm, hand, and pen without thinking out each curve and dot of written shapes.

Language’s variety dazzles. Casual, it barely makes a dent. Powerful and focused, it can rearrange our inner furniture. Words can be careful, as in “full of caring,” or as in walking a precarious line between dangerous edges. Flaming emotion rides words like stampeding horses. Inspired speech may flow like a river, perhaps from an unnamed and unknown spring. Are words then an expression, a symbol and structure pointing to something else? Or, even living story-beings with their own consciousness, substance, and direction?

Think of stranger-talk in the supermarket waiting line, intimate words in bed or in the moments before death or after birth, bureaucratic language, pet talk, baby talk, advertising language, political rhetoric, prophetic proclamation, storytelling, sign language, body language, poetry, scripture, mantra, music as language and language as music, software languages, dialoging with the wind and trees to find the way home in the north woods, the dance of bees …

Language reflecting about itself may already be problematic. More problematic is using a particular language to talk about language in general, as we will see. But perhaps language is more than flexible, is richer than we realize.

Let’s attend to this automaton language for a while. Something so effortlessly out of view is likely to hide some surprises. What can we gather from stories and reflection, maybe even intuition, about its mystery?

Language and Light

Susan Schaller stumbled onto American Sign Language (ASL) when she was 17 at a Cal State University class called Visual Poetry.[1] The class was so exuberant, so celebratory, that she fell in love with ASL, its beauty, its richness and subtlety, even though she had full hearing in both ears. After she graduated from college, a job counselor sent her to a community college to translate English into ASL for the deaf in a mixed class of deaf and hearing students.

The class was so chaotic on her first day that she was about to leave when she noticed a young man wedged alone in a corner of the room, arms folded over his chest. He looked bewildered and frightened. At the same time he was watching, intently studying the faces crowded around the class instructor as if he was trying to decipher what those people, moving their lips and gesturing, were doing.

Susan paused. There was something about this frightened man—a look of intelligence mixed with determination and fear …

She walked up to him and signed, “Hello, I’m Susan.”

Still looking worried, he hesitatingly and clumsily signed back to her, “Hello, I’m Susan.”

Wait. What?

She tried again. Same thing. He was copying her gestures instead of conversing. He didn’t seem to know what the signing meant. Maybe he didn’t know what a conversation was.

After a while she realized that he had neither spoken nor visual (sign) language. An adult in his late 20s, he was without language! How could this be in Los Angeles in the twentieth century? Probably he had managed to survive in life by copying what other people did. And he was completely deaf, so he did not know that sound even existed.

She was only 22 and not yet an expert on anything, but something in her wanted to help.

For the next four intense months the two met regularly on weekdays—she trying to teach American Sign Language to an adult who had never had any language at all. How does one do that? Many experts had said it couldn’t be done. She didn’t know if he would keep coming back to their sessions, and sometimes she wondered if she would.

One evening she had an idea: She would mime both sides of an interaction between a language teacher and a student without language instead of trying to address the man directly. At their next meeting she placed two chairs facing each other. She sat in one chair and pantomimed a teacher signing “cat” in ASL with visual props. Then she switched to the other chair and dramatized a student’s responses, from uncomprehending to ahah. Back and forth, back and forth. The young man, whose name was Ildefonso, watched from the side. This went on all week.

She remembers vividly the moment when the first breakthrough happened. Out of the corner of her eye she saw him suddenly sit up in his chair, rigid, face flushed. He began pointing frantically at different things in the room and then looking to her to sign each one. After some minutes of this he put his head down on the table and began to weep uncontrollably.

What he got, that first time, was that things have names! A world opened up to Ildefonso that he had never seen before: names, and a magical way of sharing with other people from which he had been excluded his whole life. And this was just the beginning. There was much more to learn. Languages are immensely complicated when you start from scratch at 28 years old. Besides individual objects, there are named qualities like color that are objects only in the mind. There are names for actions, not just objects. Abstract concepts like time have names. There are correct and incorrect ways—grammar—of putting these elements together into simple and then complex sentences. Written words require another leap of understanding.

Susan and Ildefonso worked together for four months, slow tedious progress mixed with sudden illuminations and a gradual equalization of their relationship, as Ildefonso began to ask for more of what he wanted to know instead of Susan trying to guess or intuit what should be next for him.

Then Susan moved on to other parts of her life, but she managed to get in touch with him again after some years. By then he had learned to communicate effectively with ASL. And she wanted to know what that first moment of discovery was like for him. “It was light!” he told her, “before was darkness, after there was light.”

It was light.

It was a whole new magical power that was opening up in him.

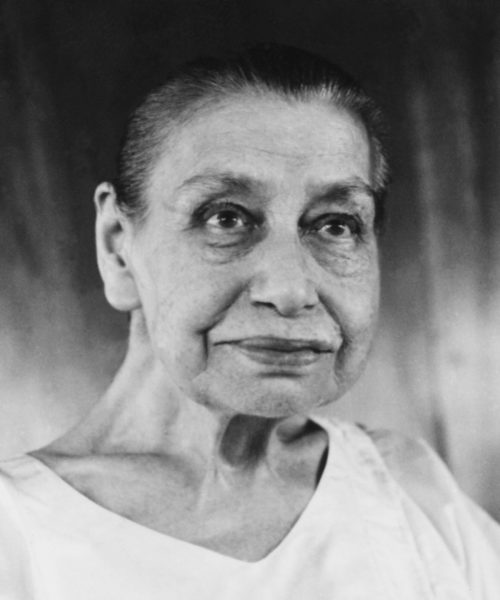

Nothing can be taught,[2] Sri Aurobindo wrote. But the teacher can help prepare the ground, the context, for something to surface in the student that was already there, but closed. Perhaps words and signs and personal relationships help create a context for something more fundamental: light, insight, meaning, an opening from within or above.

So it appears that we are also tracking intuition of some kind when we speak about language.

Shaped Earth

Once I asked my mother what special moments stood out from her years of teaching. She had taught for decades, and continued tutoring individuals after she retired from the classroom.

She described tutoring a boy, eight or nine years old, who could speak but could not read or write. All of his classmates were swimming and frolicking in the playgrounds of reading; he was alone on dry land. He couldn’t make out the relationship between the funny black marks on the paper and the words they signified.

She remembered the moment when the connection came for him. He stopped breathing. Then slowly he whispered, “So that’s how they do it!”

I wonder if his ah ha! was also an influx of light.

The connection handed him a radical new power: access to all of the libraries of the world, literatures, sciences, fantasy, humor, philosophy, drama, religion. If spoken language opens one up to the power of shaped air (breath) formed momentarily by the vocal organs of a group of humans, written language opens the door to shaped earth (material) formed in innumerable ways that can last for thousands of years.

Early writing, like early spoken language, was magic. The magic remains visible to us in great works of literature or certain moments of speech. Spelling is a part of that magic, as we might guess from the root meaning of the word, as in “cast a spell.” Even casual conversation casts nets of meaning back and forth. Considered in this way, a blessing might be called “casting a form of light.” And a vast epic poem like Savitri might be called “casting an emerging worldview of superconscious light.”

Anna and Spirit

The owners of Jukani Wildlife Sanctuary in South Africa were desperate for help with a big black leopard that they had recently received from a European zoo. The sanctuary owners were skeptical that any human could reach this snarling, unmanageable “Diablo,” as they called him; but a filmmaker who was recording segments of a film about Anna Breytenbach convinced them to call her.

The Animal Communicator[3] shows Anna sitting quietly and respectfully in view of the leopard. He becomes relaxed and attentive even the first time she approaches his shelter at the sanctuary. During that sitting she learns that he doesn’t like the disrespect implied in the name Diablo and that he will tolerate no pressure to perform for or interact with humans. The caretakers at the sanctuary could hardly believe the change in his demeanor after Anna assured him that there would be no pressure to perform and that they would called him “Spirit” in the future in recognition of his sheer beauty and power.

Anna Breytenbach[4] is a professional animal communicator from Cape Town, South Africa. She calls her work interspecies communication, a two-way “energetic transference of direct knowing and of shared experience.”[5] She finds this kind of communication accessible with any species and even with rocks and other “inanimate” matter.

In an interview she explains that it “really is live, clear and present two-way communication between myself and the animal in question,”[6] and not about learning any fancy technique. The essential preparation is cleaning out one’s internal baggage and then continuing to clean regularly. It’s about letting the ego personality recede, and being deeply present, receptive, and intentional. She describes how the “limbic bathing” she receives may eventually reach some word structures in her brain to allow the experience to form itself into words.

Perhaps here we are looking at Illdefonso’s “light” in a subtle form initially without words. We can consider intention, receptivity, response as shapes of energy felt at a more subliminal level.

But is this communication really language? Or is it telepathy or intuition? These questions seem to call for some kind of definition: What is language really? We need to pin down what we are talking about.

Let’s acknowledge the desire for definition … but also step back from this particular runway until later. Perhaps the impulse to define is also part of the automatism of a way of thinking and speaking.

Tell My Story

Jane Rosen is a celebrated sculptor and visual artist who started her artistic career in New York City. Once on a visit to Northern California, she noticed a red-tailed hawk flying over head. As she looked up at the hawk, she heard the clear words, “Tell my story!” That experience, those words, launched her life in a new direction. Eventually, she settled on the West Coast and started sculpting hawks from marble. You can see examples of her work here.[7]

One morning she awoke to her dogs barking in another room of her countryside ranch south of San Francisco, California.[8] The barking was distinctive, not aggressive or fearful, but more like “what the heck?” She got up and found them focused at a safe distance on a big black raven under a chair at the dining room table. Rosen surmised the raven was a mom looking for food. She looked at the raven, and the raven looked at her and blinked. She got a clear message from the bird: “I’m in a fix here. I don’t know how I got under this chair, and you have two big dogs there.” Rosen told the visitor that she would get her outside if she did not try to peck or claw her. As a test, she bent down and gently stroked the bird’s back. Rosen then picked her up and cradled her in her arms. The raven folded her claws under her body and put her beak down into her chest; she was completely still. Rosen carried the raven outside and put her on the porch picnic table. The raven turned, looked at her, and nodded.

There seems to be an equality in her actions as Jane Rosen tells this story. She and this wild raven became friends, the raven sometimes coming back to the porch for a visit.

Her communications go beyond animals and plants. The marble itself speaks to her sometimes as she works. In one interview she described chiseling the beak of a hawk sculpture. This is precarious work; one wrong move and the sculpture is ruined. She was doing something with the chisel she thought was stupid. “What the hell are you doing, Rosen?” she said to herself. But her hand was following a different guide. She remembered her assistant watching the process anxiously. The chisel broke off a piece of marble. Suddenly the beak was perfect. She would not have seen or dared that maneuver with her outer, intellectual mind.

Jane Rosen is articulate about her inner process. There is a going out and a going in, she says, going out to the raven, for example, or to the marble she is sculpting, and at the same time going in to her own experience of the event. She says we have a satellite dish from our knees to our shoulders where something new can come in or through from that different guide. When the two movements, out and in, come together, a fuller, truer hidden world behind the outer one comes into view. “You’re serving something else. You’re not in charge,” she says. “You’re just there and it’s moving through you, and you’re not in the way.”[9]

If you watch animals—like a cat poised in front of a mouse hole—”you see an absolute, attentive awareness with their whole being,” she says. “Mostly we’re in our heads. If you get down in your body, you have a chance” of attuning with that kind of integral awareness.

Aleut wisdom keeper Larry Merculieff agrees that we in Western culture are mostly in our heads. Disconnected, he says, dissociated from our bodies.

Glimpses of Indigenous Languaging

Larry Merculieff is a member of the last generation of Aleuts raised in the fully traditional way extending back about 10,000 years on the Pribiloff Islands in the Bering Sea between Alaska and Siberia. Although he describes that upbringing vividly in English,[10] he acknowledges how hard it is to translate his experience from his native Aleut language. This difficulty of translating from one language like Aleut, to a radically different language like English, will become more prominent as we proceed. How can Western people, with such a different upbringing and language, really grok what he is saying?

But let’s try. Slipping down into a silent receptivity that we may ordinarily find only in meditation or a solitary walk in the forest, let’s imagine a childhood where the companions and relatives of our young world are the texture of rocky soil and ice, the greens and grays of the island bush, the rhythms and smells of the sea, and the cry of the seabirds. This world is inside of us as Aleuts, because we are not called out of it to separation, dissociation, and individuality by our families and upbringing and language, but are born and welcomed into this island world, our relatives, our larger being, from birth.

When Larry was very young he had a traditional mentor, a teacher, who arranged for him to join a winter hunting party near a place frequented by sea lions. These animals stay in the water during winter because it is too cold for them on land. Even as a five-year-old, Larry wondered how the adult hunters could sit so still for hours at a time, so connected, so locked in that they knew when a sea lion would surface within range before there was any outward sign. This hunting was a matter of survival for his people, but putting it that way abstracts the situation into thought and logic. They didn’t think or reason themselves into that effort of concentration. But how did they do it?

He didn’t pose his question to his mentor or his parents. That wasn’t the traditional way. Instead, when he was six, an inspiration came to him. Early one morning he walked alone to the shoreline beneath one of the seaside cliffs, riddled, honeycombed, with the nests of thousands and thousands of seabirds. When dawn colored the landscape and water, an unfathomable chaos of tens of thousands of winged beings simultaneously calling, diving, slicing, soaring, landing, and taking off arose in the air in front of the cliff.

As he settled into an inner silence and heightened alertness that he learned from the hunting party, he noticed something. Not a single bird collided with another, not even a wing was clipped in passing! All of the birds were somehow present in each moment of flight. They were completely alive, as if a single being! Again we could say that this was a matter of life or death for their chicks. Again we can say that the birds didn’t need to create an abstract version of the situation in that way. Abstraction would have inhibited their full presence in the “chaos,” which evidently wasn’t chaos to them. It would have separated them from themselves. But they weren’t separate, from themselves or one another.

And the answer didn’t come to him in a mental abstraction either. He entered that fullness of presence in his own body. With practice, he became that. Fully present, fully embodied. “They” were him. He was in that fullness of presence in the moment.

His people call that kind of embodied presence the “real human being.” This “real human being” of the Aleuts seems to have striking similarities with what Sri Aurobindo calls the “real man” or the “true being” in a chapter of The Synthesis of Yoga called “The Soul and Its Liberation”: “When we get back to our true being, the ego falls away from us; its place is taken by our supreme and integral self, the true individuality. As this supreme self it makes itself one with all beings and sees all world and Nature in its own infinity.”[11]

How does a community live on a 43-square-mile island in the frigid Bering Sea for thousands of years, without forests, without fossil fuels, without metal, without electricity, without writing, through the midnight sun, the storms, the long dark of winter?

Not by being separate from their land.

And this is where language comes back into the picture for us. Larry says that each landscape has a particular vibration and that Indigenous languages develop from that vibration.

This “land vibration” may sound obscure or abstract to Western ears, but I have, as many of you may also, vivid recollections of the hills and soil and especially flowing waters of my childhood—even a dim longing to be back there in that, in contrast to the beautiful mountains and streams of California where I live now. Memory of connectedness to that Appalachian childhood landscape still vibrates my heart in very particular situations.

Still, how could a deep connection to the vibration of the land turn into a language, even in thousands of years?

In many Indigenous languages, words or sounds that represent the beings and relatives and flowings of the land are the human version of the sounds made by those beings and relatives. In English the sound of names like “tree” or “creek” seems arbitrary. The sound of the word “tree” has no relationship to the sound that the California black oak outside my window makes. The sound of English is separate from the landscape. In addition the sounds of American English arose on an island thousands of miles from our home here in the U.S.A.—separation multiplied.

By contrast, the word for a local tree in a native language might be the very sound that the drying leaves of that tree make when the north wind sets them dancing in the fall. The human voice imitates the sound of nature—but putting it this way surfaces the assumption that we humans and our voice are separate from this nature that we imitate. Perhaps we could say that the human voice speaks the language of that landscape, but still an implicit separation remains.

So, let’s try, less abstractly, “the human, like other beings of the land, is the land languaging.”

This is not how we speakers of English ordinarily think or speak, but we start to imagine what “being the land languaging” might mean. This kind of languaging implies an identification, an intimate participating in the process, the flow of the people’s surroundings.

Perhaps we are beginning to notice the difficulty of translating from Aleut to English. This difficulty is not unique to English.

English and other Western European languages emphasize distinction, difference, classification, and abstraction. We want to define what we are talking about. “Define” means to set boundaries around a concept, separating it out from other similar concepts. Sleet is not exactly rain or snow or hail. To define “sleet” we identify qualities that separate it from those other forms of falling water so that we know where sleet fits in the classification hierarchy. We cut that piece of the pie out so we can have a closer look at it. We often find meaning by separating. We have built a whole science that way. And we have built much of a worldwide culture on this kind of understanding.

Some, perhaps most, North American Indigenous languages privilege connection, relationship, unfolding experience, and fluidity instead.

For example, Larry describes how his people use a particular plant poison on their spears to hunt whales. The poison goes to the whale’s heart but nowhere else. A Western anthropologist might wonder how they discovered that poison and its use. Did they see some animal die after eating the plant? Was it a matter of trial and error? Did they form an hypothesis and test it over the centuries?

Questions like these come from a certain way of thinking, assuming we are separate from the land and the plants, and have to wrestle out nature’s secrets as well as we can.

It was nothing like that, Larry says. We talked to the plant, asked permission to use it and how to use it. The plant told us when to harvest the leaves or roots, how to prepare them, and how to use them. This is not metaphor; it is “everything is connected” as a way of life. Think Jane Rosen and Anna Breytenbach. Perhaps remember your own synchronicities with bird or butterfly or redwood. And imagine living within yourself and your world that way.

Jeannette Armstrong, fluent speaker of Syilx Okanagan and a traditional knowledge keeper of the Okanagan Nation, told Derrick Jensen: “Attitudes about interspecies communication are the primary difference between Western and Indigenous philosophies. Even the most progressive Western philosophers still generally believe that listening to the land is a metaphor. It’s not a metaphor. It’s how the world is.”[12]

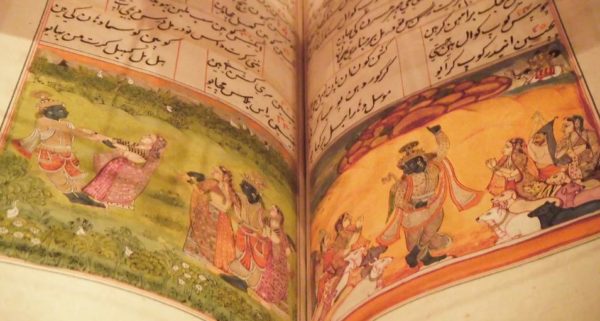

Elsewhere she wrote about how her people’s language expresses their relationship to the land, the Okanagan, where they live in what is now called British Colombia:

In the Okanagan, our understanding of the land is one in which we are not just part of the land, nor just part of the vast system that operates on the land, but that the land is us. In our language, the word for our bodies contains the word for land. Our word for body literally means ‘the capacity for land-dreaming’ — the first part of the word invokes my ability to think and dream, and the latter part of the word invokes the land. Therefore, every time I say the word for my body, I am reminded that I am from the land. I’m saying that I’m from the land and that my body is the land.[13]

We could say that language participating in earth-life this way is integral with the flowing of “the manifesting” into “the manifest.”

Owen Barfield calls this process “original participation,” where the people’s preconscious stance is that language evokes, pulls forth from the manifesting into the manifest, rather than merely refers; it is a way of being watchful in a process world of verbs rather than taking the “it- ness” of things for granted as nouns, and being careful what they speak. And when these people speak to us from within this view of “participation between perceiver and perceived, between [hu]man and nature”, their oratory and writings sound to us like poetry rather than prose.[14]

Here, language itself, its very sounding, is a powerful manifesting, not just a static and arbitrary reference to the “real thing out there” or to the meaning that the words refers to. This may suggest how Indigenous people participate in the rising of the sun and the bringing of rain in ceremony. Language is powerful here because it is experienced as an integral part of the processes of nature. Therefore care must be taken with speech, else casually spoken words may cast a form that comes into manifestation to the regret of the speaker who cast it.

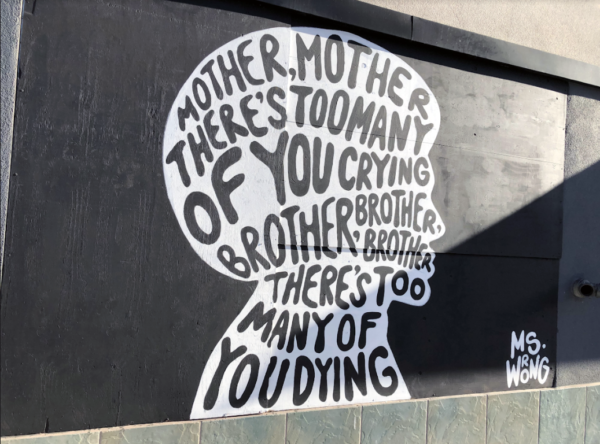

Given this depth of connection between land and language, we may better understand Mohawk[15] speaker Douglas George-Kanentiio’s lament to historian Huston Smith about the disappearance of native Mohawk speakers. Their language , he says

was developed and born in the land in which we find ourselves. We are taught that it is the language of the Earth. It is the language in which we communicate with the natural world … we are told that is the means by which we can effectively communicate with the natural world. If we don’t have that language, then we can no longer talk to the elements. We no longer can address the winds. We no longer can address the natural world, the animal species.”[16]

This discussion may also give us some sense of why Sri Aurobindo wrote how important it is for colonized peoples to retain their original language.[17] Otherwise a crucial pillar of their collective soul dissolves and their survival as a people is crippled, if not destroyed.

Dynamically Unfolding Reality

What if there was a language that takes this flow, this participatory fluidity to what would be an extreme for English speakers? People speaking Algonquin languages like Cree, Mi’kmaq, and Blackfoot say they regularly speak all day without using nouns. This is very difficult for English-only speakers to fathom. We fill our language world with things, which, grammatically, are nouns. What are we going to say if we have nothing to talk about? And things/objects/nouns are distinct from one another. A lamp is not a table, and neither is an oyster. Which is to say we fill our world with separation.

For stability.

We want to … slow down … the flow … into snapshots—things.

So that we can master them. Separately. One at a time. Or one class at a time. We keep dividing things into parts until we reach the indivisible—atoms. Oops, the atoms are divisible, composed of smaller things.

Now we’ve got them!

Oops, some of these subatomic particles have no mass! Are these things things? Are electrons really particles? The stability of the world keeps slipping away.

Some English speakers call native languages “verb-based” or “process languages” because they express the world as flux, as movement, as flow of experience instead of as a stable of objects. A simple example: Imagine an English-speaking mother directing her toddler’s attention to a bouncing ball. The mother would likely say something like, “Oh, look at the ball!” Whereas the Cree-speaking mother might say the equivalent of, “Oh, look at the bouncing!” Bouncing is a moving. It’s a wave, not a particle. Then consider how important the directing of attention is in learning one’s culture, one’s place in the world. It tells us what is important, where to focus, even what is real. The movement, the flow comes to the foreground in these languages—and in their worldview.

The title of the film Dances with Wolves is also the name of the film’s hero. “Dances” is a verb that has usurped, so it seems, the proper place of a noun. The person is a verb!

Here is Joseph Rael (Beautiful Painted Arrow) describing some examples of his Tiwa language of the Picuris Pueblo in New Mexico:

Tiwa words convey a dynamically unfolding reality that is constantly in process. The Tiwa language has no nouns or pronouns, so at Picuris things don’t exist as concrete, distinct objects. Everything is a motion and is seen in its relationship to other motions …

For instance, a cup is tii, but tii likewise means crystallized awareness, or awareness that is in the process of crystallizing and uncrystallizing. That cup is not fixed. In Tiwa it is a continual unfolding of tii, and tii means “the essence of the power of crystallization that is influencing awareness” and that awareness is the awareness of holding something in, like a spoon, or like tea or coffee. That coffee or tea that is in the cup is not static, either, but it’s also in continuous motion.

Of course, “tii” is not a noun or a pronoun, but a verb; therefore, it means not a cup but a cupping, the holding of energy in the process of cupping, and it is cupping another energy that is in the process of being coffee. Everything is a process in relationship with another process.[18]

Trying to carry this change of focus into all of the other “things” that we speak and think about during the day quickly becomes mind-boggling for the English speaker, but perhaps these process languages more completely catch the nature of substance in the manifestation that Sri Aurobindo wrote about below in English:

All substance of being in Space is a flowing stream not divided in itself, but only divided in the observing consciousness because our sense faculty is limited in its grasp, can see only a part and is therefore bound to observe forms of substance as if they were separate things in themselves, independent of the one substance.[19]

No Nouns No Verbs

To take this sense of flow further, let’s focus for a bit on a language that not only has no nouns, but also no verbs, in fact no words, and no vocabulary in the English and European languages sense of these structural elements. This presents a challenge not only to our English medium but also to our science of linguistics itself, which largely presumes that the structure of Western European languages—subject/noun, verb/action, object/noun—is universal. People who study history from a lens other than Western will not be surprised by this presumption of universality, which so often hides a presumption of superiority.

Native Blackfoot speakers and professors Leroy Little Bear and Ryan Heavy Head wrote an essay some years back with the tongue-in-cheek title of “A Conceptual Anatomy of the Blackfoot Word.”[20] They start off the piece—written in English, but sprinkled with Blackfoot “soundings”—with the admission that the title is a contradiction, because the Blackfoot language does not have anything that corresponds to “word” in English or other European languages. Nor does it have anything corresponding to the word or concept “anatomy.” Using “anatomy” in the title of their article as a metaphor to visualize the components of “word” sounds plausible to English speakers because of the way we think and speak. We break things down into their component parts to understand how they are put together and how they work. Blackfoot, however, is not concerned with “things” composed of other things, but with experiences that manifest out of a flux of movement. It doesn’t have sentences (a bounded set of words including a verb and a related noun). Its emphasis is not on difference and distinction but on flow, flux, and patterns of experience and relationship.

If Blackfoot doesn’t use words and sentences, how does it work? Not being a Blackfoot speaker, I’m not about to try to tell you, but you can look at the article cited above for a taste. My best guess as a metaphor is jazz, which uses specific scales, and the notes and octaves in those scales. An isolated note by itself is not jazz, but its jazz meaning emerges in the improvised and momentary relationship among notes as they are played, the voices and instruments that are sounding them, the musicians that are playing the instruments, and the physical and emotional circumstances in which they are played. This web of relationships becomes a flow of information and energy.

It may be a surprise that the Blackfoot language and way of understanding make describing quantum mechanics almost a breeze, according to Leroy Little Bear, who has been fascinated with science, and physics in particular, since childhood.

David Bohm, the American physicist and protégé of Einstein, was long in search of a non-mathematical verbal language that could make sense of quantum mechanics. David and his friend J. Krishnamurti tried to create such a language, called Rheomode,[21] but David was not satisfied with it.

It happened that F. David Peat, an English physicist, was both a friend of and collaborator with David Bohm and also a friend of Leroy Little Bear. David Peat arranged a meeting of his two friends along with a small gathering of other relatives, Indigenous elders, and Western scientists in Michigan in 1992. This gathering was the beginning of what became the annual Language of Spirit dialogs between Indigenous elders and wisdom carriers on one hand and Western physicists, poets, and philosophers on the other—perhaps the first, or one of the first times that these groups sat together with an attitude of full mutual respect.

So Dr. Leroy Little Bear, a Blackfoot elder and university professor fluent in his mother tongue who loves physics, and Dr. David Bohm, a celebrated American physicist who was interested in language, finally got a chance to meet and talk on equal terms, just two months before David’s death. In a video, Leroy recalled David Bohm’s question about his unsatisfactory attempt to create a nonmathematical language to explain quantum mechanics. “What should I do?” he asked Leroy. With a twinkle in his eye, Leroy remembered his reply: “Learn Blackfoot.”

Now that we know what a human language is, not to mention animal and plant languages …

OK, that’s a joke. We are deep in the linguistic woods now, so to speak. And we want an answer that satisfies our assumptions about language and the way we view “things” with the help of our language—what the heck is a language after all? We in the West have assumed that we knew what languages were. We developed our science of linguistics based on our own European and Indo-European languages. This version of linguistics doesn’t fit North American Indigenous languages and probably many other languages in the world. There is a gap that hasn’t been bridged not only between languages but between worldviews. “A Conceptual Anatomy of the Blackfoot Word” openly acknowledges that translations into English of Blackfoot examples are “loose” and that its mission is not to create a bridge—to translate—between two mutually incompatible worldviews and language structures. “Instead, our aim is to convincingly relay merely the existence of another intellectual tradition”[22] and its potential value when clearly “the imposition of Western methodology and theoretical models upon worldwide phenomena has not worked.”[23]

Maslow’s Surprise

In the summer of 1936, Abraham Maslow, originator of the motivational theory of the hierarchy of needs, visited the Siksika (Blackfoot) reserve for six weeks. Evidently he went there to test his theory that social hierarchies are maintained by dominance of some groups over others.[24] To his surprise, he found stark differences between the dominance patterns in his own society and the huge levels of cooperation, minimal inequality, and high degrees of social satisfaction at Siksika. He estimated that “80–90% of the Blackfoot tribe had a quality of self-esteem that was only found in 5–10% of his own population.”[25]

Large differences of life satisfaction between Western societies and relatively whole Indigenous societies of contemporary or colonial times is not a recent discovery. In fact leaders and thinkers of American Indigenous societies leveled devastating critiques at both American colonial societies and European societies as far back as the sixteenth century. Some scholars, like anthropologist David Graeber and archeologist David Wengrow, authors of The Dawn of Everything,[26] contend that the critique of Native scholars like Wendat leader Kondiaronk (c. 1649–1701) about poverty, homelessness, private property, slavery, and domination of the many by the few in Western Europe had a profound impact on the development of norms of freedom, democracy, and equality among European thinkers of the Enlightenment.

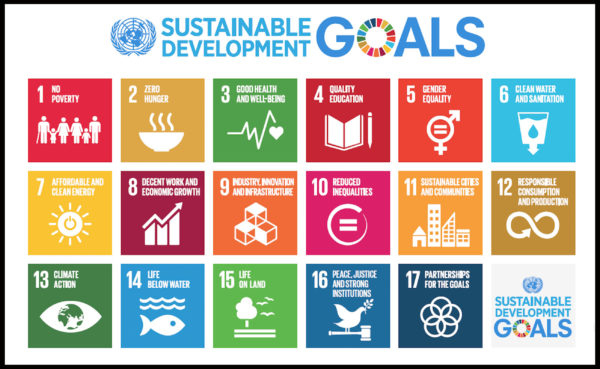

This critique has been growing again in our time, aimed at the devastation of world peoples, life forms, and natural systems by Western colonial and industrial society.

Old assumptions of separation, domination, superiority, and privilege are sagging as submerged voices from all over the world resurface to call for a different, integral approach to individual, social, natural, and global relationships.

Language and Worldview

We have been following forms of language moving from particular to more universal. We have seen some of the power and shapeshifting of this magician language.

Following stories like these of the many-colored exuberance of language brings into focus the narrowness of aspects our Western worldview and limitations of our European languages. It may also suggest to us that a deeper appreciation of lifeways and languages of connection may be valuable for yoga and for humanity in a troubled contemporary world dominated by worldviews and languages of separation. Noticing how language mirrors the way its speakers think and act, its grammar almost demanding that they think a certain way, suggests that language itself may be one lever for more integration.

There is one lurking obstacle to widening our view about these worldviews and languages of connection. Because we think and speak a certain way, and those ways are effective to a certain degree, we’re likely harboring a belief or assumption that our kind of science, astronomy, for example, cannot be replaced by some native creation story. Oakley Gordon, Ph.D., author of The Andean Cosmovision[27] about the precolonial practices and worldview (cosmovision) still present among some of the Quechua people of the high Andes in South America, tackles those implicit assumptions and beliefs directly. He points out that a worldview like the that of the Quechua is not simply a “primitive” or inferior version of our modern worldview without the superstitions and illogical suppositions removed. It may be qualitatively different than the Western way of understanding or even reasoning—and equally valid. And more than valid—precious, a unique and rich contribution of knowledge, insight, method, and delight for the human family.

Somewhere Dan Moonhawk Alford[28] (1946-2002), beloved professor of linguistics at the California Institute of Integral Studies for many years, suggested that Indigenous languages bring a participatory energy that is creative and suggested how this might be possible also in English, Sri Aurobindo’s preferred language of writing. Participatory engagement appears easier in Indigenous languages because the structures (grammar) of participation and manifestation are already present in the language. But with intention, like Ildefonso’s desire to have language communication, the automatic structures of one’s original language can become conscious. Sri Aurobindo’s poetry suggests that conscious linguistic structures can become evocative for a transformed consciousness. Because worldview and language are so tied together, reading Savitri and Sri Aurobindo’s other works is a doorway into his vision and consciousness, his operating worldview.

Language Love

Sri Aurobindo wrote that a “greater era of man’s living seems to be in promise … But first there must intervene a poetry which will lead him towards it from the present faint beginnings.”[29] And Mother repeatedly voiced her dissatisfaction with French and English to express the transformational experiences of the body. She once implied that a new level of consciousness would bring a new language when she spoke about the problems created by the many distinct languages of India: “Unity must be a living fact and not the imposition of an arbitrary rule. When India will be one, she will have spontaneously a language understood by all.”[30]

Perhaps some of these future languages are just waiting for appropriate conditions to appear.

J.R.R. Tolkien (1892–1973), author of The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings, was a lover of language. This anyone could gather by the sheer beauty, the magic of his writings. One could get the same impression with a glance at his life.[31] By the time he started high school, he knew English, Greek, Latin, French, and German. In high school, he fell in love with Gothic, an ancient European language that became extinct in the eighth century. Tolkien wrote of Gothic that for the first time he was learning a language purely out of love, not for its utility nor for the sake of the literature it carried. He would even show up at debate events in school dressed as an envoy from the Goths and regale the audience in Gothic!

A parade of language proficiency followed during his life: Middle English, Old English, Finnish, Italian, Old Norse (Old Icelandic), Spanish, Welsh, and Medieval Welsh. He became familiar with many more.

When he discovered the Finnish language in college, he was so inspired by the musical quality of its “long, loping words,” that he began to work, from scratch, first on a whole new language that he eventually called Quenya, and then on another new language, parent to Quenya, called proto-Quenya.

Something similar happened to him when he was introduced to Welsh. He started developing still another new language based on his love of the beautiful sounds of the Welsh tongue, eventually naming the new language Sindarin, another offspring of proto-Quenya, but quite different from its sibling, Quenya.

How does someone create a new language and also a proto-language parent of that new language? Is that even possible? Tolkien’s experience was not that he was creating new languages, but that he was discovering them. In some sense, somewhere, they already existed.

Quenya and Sindarin were elvish languages and became, by Tolkien’s own account, the sources of his writings about the Elves and Middle Earth. He did not start with the stories, the people, or the worldview that he developed in The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings. The stories came through the languages. To come into a fullness of being, the languages needed both people who spoke them and a way of understanding life embedded in the languages.

How did he do it? His good friend, C.S. Lewis, once wrote that Tolkien lived inside language. Tolkien wrote, “Always I had the sense of recording what was already ‘there,’ somewhere, not of ‘inventing.’”

Tolkien’s experiences suggest that languages have a life of their own in some other realm. They can be discovered before one knows anything else about them. They can carry stories and their own unique metaphysical understandings of the way things are.

Mother’s difficulties with language during her yoga of the cells may have arisen because the languages for the transformation of the body have not yet been downloaded by humanity. Could the transformation of the body be assisted by a blending of the progressive urge of Western languaging and the balancing and harmonizing languaging of Indigenous peoples?

John Robert Cornell currently serves on the Collaboration Editorial Advisory Board and the Collaboration Steering Committee.

Notes

[1]. This material is synthesized from Susan Schaller, A Man Without Words (New York: Summit Books, 1991) and from an interview by Richard Whittaker at https://www.conversations.org/story.php?sid=200

[2]. Sri Aurobindo, Early Cultural Writings, Complete Works of Sri Aurobindo (CWSA), vol. 1 (Pondicherry: Sri Aurobindo Ashram Trust, 2003), p. 384.

[3]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=T2vhV63lx2k

[4]. Anna Breytenbach’s website is https://animalspirit.org.

[5]. Most of this section is from an interview of Anna Breytenbach at https://batgap.com/anna-breytenbach-transcript/

[6]. Ibid.

[7]. https://www.janerosen.com

[8]. Details of this story can be found at an interview with Jane Rosen by Richard Whittaker: http://www.dailygood.org/story/599/looking-with-your-whole-body-richard-whittaker

[9]. Ibid.

[10]. The material in this section comes from David E. Hall, Native Perspectives on Sustainability: Larry Merculieff (Aleut):

Click to access Larry_Merculieff_interview.pdf

[11]. Sri Aurobindo, Synthesis of Yoga, CWSA, vols. 23–24 (Pondicherry, Sri Aurobindo Trust, 2007), p. 439.

[12]. Quoted in Derrick Jensen, A Language Older than Words (White River Junction, VT: Chelsea Green Publishing Company, 2004), pp. 67-68. Libby Digital version.

[13]. Jeanette Armstrong, “An Okanogan Worldview of Society.” Living Earth Community: Multiple Ways of Being and Knowing (Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2020), p. 164.

[14]. Dan Moonhawk Alford, “Manifesting Worldviews in Language,” So What? Now What?, ed. by Matthew C. Bronson and Tina R. Fields (Newcastle on Tyne, UK: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2009), p. 303.

[15]. Mohawk is the name of one of the nations and languages of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy located in what is today northeastern United States and southeastern Canada.

[16]. Huston Smith, “Native Language, Native Spirituality, From Crisis to Challenge,” A Seat at the Table, ed. Phil Cousineau (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007), p. 83.

[17]. Sri Aurobindo, The Human Cycle, The Ideal of Human Unity, War and Self-Determination, CWSA, vol. 25 (Pondicherry: Sri Aurobindo Ashram Trust, 1997), pp. 514–517.

[18]. Joseph Rael, House of Shattering Light (San Francisco, Council Oak Books, 2003), p. 124.

[19]. Sri Aurobindo, The Life Divine, CWSA, vols. 21–22 (Pondicherry: Sri Aurobindo Ashram Trust, 2005), p. 517.

[20]. Leroy Little Bear and Ryan Heavy Head, “A Conceptual Anatomy of the Blackfoot Word,” ReVision, A Journal of Consciousness and Transformation, Vol. 26, No. 3, pp. 30–38.

[21]. For more on Rheomode, see F. David Peat, Blackfoot Physics (Boston, Massachusetts: Weiser Books, 2002), p. 238.

[22]. Little Bear and Heavy Head, p. 32.

[23]. Ibid., p. 38.

[24]. Teju Ravilochan, The Blackfoot Wisdom that Inspired Maslow’s Hierarchy—The Esperanza Project: https://esperanzaproject.com/2021/native-american-culture/the-blackfoot-wisdom-that-inspired-maslows-hierarchy/

[25]. Ibid.

[26]. David Graeber and David Wengrow, The Dawn of Everything, A New History of Humanity (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2021).

[27]. Oakley E. Gordon, The Andean Cosmovision (Publisher: Oakley Gordon, 2014).

[28]. I can no longer find the reference.

[29]. Sri Aurobindo, The Future Poetry, Complete Works of Sri Aurobindo, vol. 26 (Pondicherry: Sri Aurobindo Ashram Trust, 1997), p. 221.

[30]. The Mother, Words of the Mother—I, Collected Works of the Mother, vol. 13 (Pondicherry: Sri Aurobindo Ashram Trust, 2004), p. 363.

[31]. Oakley Gordon, “The Path to Faërie: Part 1” provided most of the material about Tolkien in this section. See https://salkawind.com/blog/archives/1863#stalactites