Collaboration Journal

Special Feature

Yoga in Crazy Times

PHILIP GOLDBERG

This article appeared in Collaboration journal, Vol. 45, Nos. 2–3, Fall 2020–Winter 2021

EVER SINCE MY NEW BOOK WAS RELEASED in August, I’ve been congratulated on my impeccable timing. What better time for a title like Spiritual Practice for Crazy Times? The truth is, I deserve about as much credit as a gardening shop that sells shovels does when a blizzard hits. The book was conceived this past spring, when life in America was already pretty crazy; the final editing and proofreading were completed this past winter, when the coronavirus was largely confined to Asia and the phrase “shelter-in-place” had not yet been uttered. I’m happy to accept credit for producing a useful book, but I can’t claim to have known just how insane the world would become by the time it was published.

In the early days of 2019, a little more than halfway through the Trump era, I began to hear normally stable and happy people say that current events were making them anxious, worried, depressed, bewildered, enraged, or otherwise discombobulated. I knew many of those people to be genuinely spiritual. They included earnest veterans of one path or another who had kept up a daily sadhana for decades; relative neophytes who had set foot on their paths only recently; and dabblers with a sincere spiritual orientation to life but complacent about engaging that impulse. To my surprise, even some members of the first group were neglecting their practices. When I asked why, I heard—in addition to the usual excuse of being too busy—two reasons that reflected the challenges of this period in history.

One set of people said they were too agitated, too stressed out, and too unsettled by what was going on in the world to meditate (or practice yoga, or mindfulness, or prayer, or whatever else their sadhana might consist of). A second consisted of activists who were trying to fix the social conditions that upset them. They were getting involved in political campaigns, raising money for social justice groups, organizing demonstrations, blogging, or otherwise trying to make a difference. They saw spiritual practice as a luxury they couldn’t afford. In my book, I quoted a woman who gave voice to a sentiment I’d heard from others as well: “I don’t want to waste time on my inner life when there’s so much at stake out there.” She didn’t want to lose the anxiety and righteous anger that were driving her efforts; she feared being neutered by spiritual practice.

I found both arguments understandable but radically misconceived, and I said so in an article. About the first set of objections I wrote by way of analogy that taking a shower can be good for our well-being when we’re relatively clean, but it’s absolutely vital when we’re filthy. Waiting till we’re calm and content before sitting to do a centering practice is like showering only when we’re clean, or seeing a doctor only when we’re feeling well. Meditation, yoga asanas, breathwork, prayer, mindfulness—they don’t require calmness as a prerequisite; they produce that calmness. You can’t be too agitated to do the very things that are designed to reduce agitation. I argued that it’s precisely in conditions of turbulence and turmoil that we need the refuge of spiritual practice the most.

To the honorable and compassionate individuals who were busy making the world a better place, I said that the spiritual methods developed by the rishis of old and the mystics of all traditions are not escape mechanisms. They don’t necessarily lead to withdrawal or disinterested detachment. They’re not like tranquilizer darts or the drugs that turn mental patients into docile creatures. They don’t make you a religious fanatic who thinks God will take care of everything so we don’t have to bother, or a renunciate who sees the material world as a mere illusion and the human drama as a stage play they can witness without playing a role. On the contrary, I proposed, spiritual practices can be a foundation for engaged citizenship— and a platform for soulful, compassionate, effective action. It may seem too obvious to mention, but it was necessary to remind my activist friends that Mahatma Gandhi, Martin Luther King Jr., Jesus, and countless venerated saints were social warriors whose roots were planted firmly and deeply in spiritual soil.

Spiritual practices can be a foundation for engaged citizenship—and a platform for soulful, compassionate, effective action. It may seem too obvious to mention, but it was necessary to remind my activist friends that Mahatma Gandhi, Martin Luther King Jr., Jesus, and

countless venerated saints were social warriors whose roots were planted firmly and deeply in spiritual soil.

The article was well received and led to conversations with the publisher of my previous book, Hay House, about expanding the core premise into a book.

Faced with filling a couple hundred pages mostly with practical tools, guidelines, and instructions, I began harvesting every practice I’d learned about over half a century. I ferreted out other methods to fill the gaps in my own knowledge base, drawing mainly from the yogic tradition. I favored techniques that have been validated by studies in psychology and neurophysiology.

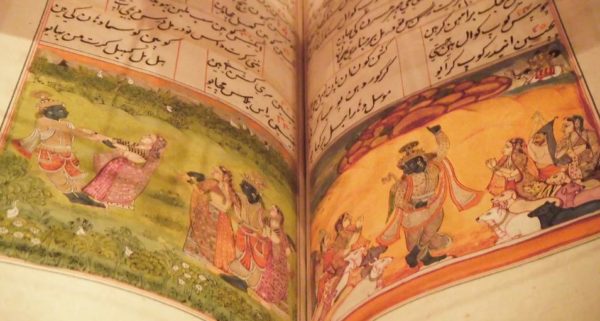

As a guiding framework, I was immediately drawn to two passages from the Bhagavad Gita that had hit me like lightning bolts in the early days of my path, and have held up ever since. The first is from chapter 2, verse 38, when Krishna tells Arjuna that it’s possible to maintain “equanimity in gain and loss, victory and defeat, pleasure and pain.” When I read that for the first time, circa 1968, the suggestion that one might achieve a state of unruffled, composed, imperturbability in the midst of life’s ups and downs blew my troubled mind. It was enough of a promise to make me dive more deeply into the spiritual teachings of the East, and to try out the yogic technologies that, I came to realize, were the keys to developing that desired equanimity. Soon enough I took up transcendental meditation (this was only months after the Beatles put it on the global map and made their watershed journey to India).

I discovered quickly that daily practice did give me more equanimity. The inner calm from meditation carried over when I went about my day, at least for a while, like a sponge staying wet for some time after it’s been soaked. In my youthful naiveté, I expected to soon get to a point where I’d never ever again get upset by setbacks. I’d be immune to the ravages of life. I’d be above it all, supremely unattached, in the world but not of it, soaked in peace and bliss at all times, no matter what.

Imagine my surprise. Needless to say, human life being what it is, shocks, upheavals, losses, crises, and ordinary annoyances continued to erupt. However, as time went by I realized that I did, in fact, have more equanimity at those times than I had in the past, and when I lost it—as I did often enough—I regained some measure of equilibrium fairly quickly. That personal observation, I was pleased to discover, has been shown in studies to be typical of long-term practitioners of meditative methods.

Sri Aurobindo referred to the quality I’m calling equanimity as “perfect equality.” In The Synthesis of Yoga, he says, “The very first necessity for spiritual perfection is a perfect equality. Perfection in the sense in which we use it in Yoga, means a growth out of a lower undivine into a higher divine nature.” He described it as “putting on the being of the higher self and a casting away of the darker broken lower self or a transforming of our imperfect state into the rounded luminous fullness of our real and spiritual personality.” He called it “a means by which we can move back from the troubled and ignorant outer consciousness into this inner kingdom of heaven and possess the spirit’s eternal kingdoms … of greatness, joy and peace.”1

And so, when I started outlining my book in 2019, that Gita verse became a lodestone. My goal was to help people access the source of equanimity within themselves, by opening up to what I call a sanctuary of peace within—to absorb it, sustain it, and carry it with them in good times and bad. This, it should be obvious, is especially important in chaotic times like ours, when gain and loss, victory and defeat, pleasure and pain are being experienced en masse in unpredictable and unprecedented ways.

The second Gita passage that has guided my life and also framed my book is from chapter 2, verse 48. Like every sentence in the Gita, it’s been translated in dozens of ways, but they all come down to the pithy version I favor: “Established in Yoga, perform action.” I’ve never found a more concise and powerful formula for living.

Having grown up in a secular, quasi-Marxist household in which religion was the opium of the masses, I had an abiding suspicion that the Eastern philosophies that seemed so rational, empirical, and practical would let me down by lapsing into dogma—or by asking me to turn my back on worldly life. I knew I was not cut out for either renunciation or believing in anything on faith alone. But here was Krishna, the voice of the divine, saying that responsible, dynamic action was not to be avoided. And if the words themselves weren’t convincing enough, the context certainly was. The message was delivered to a warrior, Arjuna, and he wasn’t being told to ride off to an ashram or settle into a Himalayan cave. Rather, he was implored to get off his butt, pick up his weapons, and vanquish the bad guys who threatened his civilization. It doesn’t get more dynamic or worldly than that.

I call it the Spiritual Two-Step: 1) Turn within, get immersed in the silent core of Being, and ground yourself in the unified consciousness that defines yoga, and 2) Come out better equipped to perform your duties, fulfill your responsibilities, and engage human life to the fullest.

But first, the divine messenger said, establish yourself in yoga. I call it the Spiritual Two-Step: 1) Turn within, get immersed in the silent core of Being, and ground yourself in the unified consciousness that defines yoga, and 2) Come out better equipped to perform your duties, fulfill your responsibilities, and engage human life to the fullest.

With those verses as a touchstone, I felt confident as an author to present spiritual practice not as just a refuge in crazy times, but as a strategy for practical living—not merely a rest stop, but a refueling station; not just an escape valve, but a launching pad from which to spring into action.

To be fair, there are plenty of renouncers in spiritual circles, not only vow-taking monks and nuns, but people who are reclusive by nature and whose paths draw them to disengage as much as humanly possible from the world’s travails. But even India’s wandering sadhus have to feed and shelter their bodies; most monastics live in communities and perform works of service to others; and dedicated householders have to manage their relationships with family members, neighbors, colleagues, and others. Whatever our degree of worldly involvement, the truth of that two-step applies: transformative spiritual practices tend to make people calmer, clearer, wiser, more compassionate, more empathetic, and more discerning than they would otherwise be. This does not, of course, suggest that regular sadhana will turn ordinary seekers into geniuses, perpetual winners, or saints. But experience and research clearly indicate that practice improves the odds that our actions will be more productive, harmonious, and benevolent—and less likely to overwhelm our inner stability.

As Sri Aurobindo puts it in Essays on the Gita, the state that Krishna points Arjuna to is not one of “disinterestedness” or “dispassionate abnegation.” How could it be? Would you want a soldier who’s protecting your loved ones not to care? Yes, you’d want him to be unattached to the fruits of his actions, as the Gita teaches. But indifferent? Certainly not. Rather, says Sri Aurobindo, “it is a state of inner poise and wideness which is the foundation of spiritual freedom. With that poise, in that freedom we have to do the ‘work that is to be done,’ a phrase which the Gita uses with the greatest wideness including in it all works … and which far exceeds, though it may include, social duties or ethical obligations.”

It’s analogous to the state of cool composure we look for in athletes when the game is on the line; in leaders when decisions have to be made in a crisis; in parents when kids are in trouble; and in ourselves at all times, but especially in emergencies. No guarantees, of course, but the evidence suggests that such an inner state can be cultivated. We may never achieve the wished-for perfection, but we can at least creep closer to it inch by inch, making fewer mistakes along the way.

That’s the practical, everyday take on “Established in Yoga, perform action”—and most readers of a book like mine will relate to it. But in truth, the Gita calls us to a higher perspective and a greater purpose. I allude to it in the final chapter, titled “Sacred Citizenship: Giving Back from the Inside Out.” As I said earlier, I completed the book before the COVID-19 lockdown took hold, and before all the astonishing and unsettling events during this past summer of our collective discontent. I assumed early on that when the book was released, in August 2020, the presidential election would be heating up and the crazy world would be even crazier. No one knew it would be this insane, of course, but I’m glad I included my humble appeal for spiritual practitioners to take seriously their role as citizens. Sri Aurobindo alluded to the reason that’s so important:

The Gita does not teach us to subordinate the higher plane to the lower, it does not ask the awakened moral consciousness to slay itself on the altar of duty as a sacrifice and victim to the law of the social status. It calls us higher and not lower; from the conflict of the two planes it bids us ascend to a supreme poise above the mainly practical, above the purely ethical, to the Brahmic consciousness. It replaces the conception of social duty by a divine obligation. The subjection to external law gives place to a certain principle of inner self-determination of action proceeding by the soul’s freedom from the tangled law of works.2

Not everyone is a social activist, of course, but we can all do something, however seemingly insignificant, to make the world a better place. We can all access the silent source within and listen to the voice of higher wisdom, or feel the faint stirring of a conscience that’s in tune with divine intent, and then act with strength and compassion in whatever sphere of life we’re drawn to. At this moment in history, we are all Arjunas, and every gesture counts. I concluded the book, and I’ll conclude this offering (which I’m honored to have been asked to contribute), by quoting the Buddha: “Do not overlook tiny good actions, thinking they are of no benefit. Even tiny drops of water in the end will fill a huge vessel.”

Notes

- Collected Works of Sri Aurobindo, Vols. 23-24, pp. 698, 699

- Collected Works of Sri Aurobindo, Vol. 19, p. 35

PHILIP GOLDBERG is the author of numerous books, including the award-winning American Veda, the biography The Life of Yogananda, and Spiritual Practice for Crazy Times. A popular public speaker, he blogs on the Spirituality & Health website, cohosts the Spirit Matters podcast, and leads American Veda Tours to India. His website is philipgoldberg.com.

Title image and smaller images derived from it: Elizabeth Teklinski

Philip Goldberg photo and books: Philip Goldberg

All other images: MaxPixel, https://www.maxpixel.net/

Subscribe to Collaboration

Collaboration explores the vision and work of Sri Aurobindo and the Mother, the theory and practice of Integral Yoga, and themes such as consciousness, emergence, and transformation. To subscribe, visit https://www.collaboration.org/journal/subscribe/